The Walls and Abyssess of Fortress North

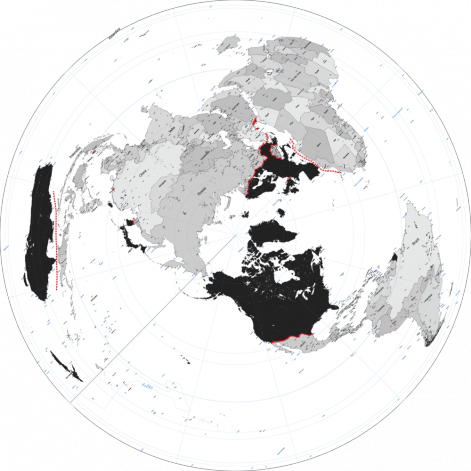

The easiness of traveling within the Globalized North for its citizens only equals the difficulty for someone to access this part of the world. The map presented here attempts to illustrate this antagonism between Fortress North and the rest of the world. Schengen, the United Kingdom, Ireland, Cyprus, Israel, North America, Japan, South Korea, Taiwan, Hong Kong, Singapore, Australia and New Zealand form the Globalized North and their borders with other countries are militarized to insure the control of migration towards them. The following list will briefly describe the numerous apparatuses that materialize borders, control bodies, and sometimes even see the latter die.

United States – Mexico border: The construction of a 14-foot high wall over 600 miles between both countries was ordered by the George W. Bush administration in 2006 under the Secure Fence Act. Migrants who manage to cross its securitarian line often have to cross dozens of miles of desert and risk being shot by civilian border vigilantes. Every year, about 500 people die during their clandestine crossing of the border, most of them of dehydration. At its Western extremity, the wall ends in the Pacific waters and thus separates the beach of Tijuana and the militarized Border Field State Park.

Mediterranean Sea: The sea that separates Africa, the Middle East and Europe is an abyss where thousands of migrants die from trying to reach the coasts of Spain, Italy or Greece (about 22,000 deaths since 2004). The Mediterranean Sea is nonetheless highly militarized; islands like Lampedusa or Malta have been historically used as Allies’ bastions in the control of North Africa during the Second World War. Between March and October 2011, NATO navy and air force also attacked the Qaddafi administration in Libya, as well as its supporters. The control of the sea is crucial for Fortress North, since it conditions the access to the Suez Canal both for container and hydrocarbon ships from the Middle East and Asia, and for military ships operating in the Indian Ocean and the Persian Gulf.

Fortress Israel: Israel operates as a militarized colonial outpost of Fortress North in the Levant since 1948. Its borders operate under the paradox to be simultaneously rigid and malleable. Its army occupied the Sinai Peninsula from 1967 and 1982, as well as South Lebanon between 1982 and 2000. The fence that separates it from Syria is built in the Eastern parts of the Golan Heights, occupied since 1967. The infamous “Separation Wall,” also called Apartheid Wall, separates most Palestinians of the West Bank from the rest of Palestine, including Jerusalem, while an important amount of Israeli civil settlements in the West Bank are situated on its Western side (where the malleable function becomes important).1 As for the Gaza Strip, it is separated by a highly militarized border from the rest of Palestine and Egypt, the Israeli Navy sealing the maritime border, thus condemning 1.8 millions of Palestinians to live in what has been rightfully called “the largest prison on earth.”

Cyprus’s Demilitarized Zone (DMZ): The United Nations demilitarized Buffer Zone in Cyprus has been implemented in 1974 after the Turkish invasion that split the island into two parts, although the Republic of Cyprus is still internationally recognized as legal sovereignty over the entirety of the territory. Like most demilitarized zones, its borders are very much militarized, including the British military base of Dhekelia in the East of the zone.

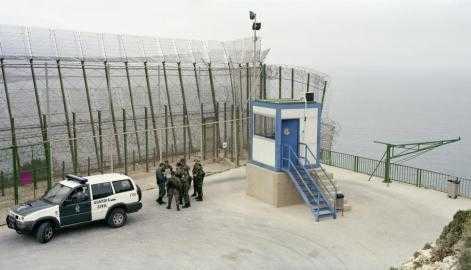

Spanish Enclaves of Melilla and Ceuta: The strait of Gibraltar presents the curious geopolitical characteristics of being framed by the British enclave of Gibraltar in Spain and the Spanish enclave of Ceuta in Morocco. A bit further east along the Moroccan coast, we find another Spanish enclave, Melilla. Because of their particular geographical situation which is deemed to favour immigration, both Ceuta and Melilla are surrounded by high, policed fences punctuated by watchtowers. Despite the risk it represents, groups of African migrants occasionally attempt to climb up without being caught by custom police patrols. As often in such abundance of police/military technology and its architectural means, we can wonder if the budget allocated to them could not serve instead to create the hospitality sought by refugees and migrants.

Schengen Space: Implemented in 1990, this European space without internal border controls that now counts 26 countries (including Iceland, Norway, and Switzerland, which do not belong to the E.U.) can be characterized by its contrastingly strict controls at its periphery. The Schengen strategy also includes a strong effort of “externalization” of its immigration policy to neighboring countries where migrant passages are important, like Serbia or Bosnia Herzegovina. Essentially these countries are offered applicants' status to the European Union if they first undertake the sub-contracting task of controlling migration towards the Schengen area. The militarized architecture of Schengen’s borders is, however, less present in its border, than in its administrative system of detention and expulsion of migrants judged as “clandestines”. Whether in Lampedusa, Calais or Belgrade, the migrant detention centers are nothing less than a carceral environment with unhealthy conditions for the bodies they forcefully imprison.

Korea’s Demilitarized Zone (DMZ): Created in 1953 following the Korean Armistice Agreement, this 250-km long and 4-km wide territory separates the Democratic People's Republic of Korea (North) and the Republic of Korea (South). Both borders of this zone are heavily militarized but the zone also counts special-status villages whose architecture ostensibly shows their supposed prosperity to the other side.

Australia’s Maritime Barrier: In its current immigration policy that aims to drastically reduce and criminalize clandestine arrivals in the country, Australia can count on its island territorial characteristics. In 2014, the Abbot administration started a large communication campaign paired with the military, Operation Sovereign Borders, in 17 languages to discourage any attempt by asylum seekers and undocumented migrants to reach the country. One poster and its video narrative by military commander of the operation, Angus Campbell, in particular shows a dangerous sea with the words “No Way. You Will Not Make Australia Home.” A graphic novel was also issued and it depicts the alleged story of an Afghan asylum seeker and the tumultuous fate of hardship that awaits him while trying to reach Australia. Like Schengen, the country counts many migrant detention centers, some of which are delocalized on remote islands, such as Christmas Island or Nauru Island, more than 1,000 kilometers from Australia.

Fortress North is thus a territory on which the free circulation of its citizens strongly contrasts with the difficulty others experience to access it or inhabit it with an undocumented status. Although the map presented here insists on its walled and abysmal borders, we should insist that the architecture of this fortress also intervenes within and beyond its territory. Asylum seekers centers, migrant detention facilities, and other administrative processing sites, where migrant bodies are condemned to wait for weeks or months, often in extremely precarious conditions, are the main architectural embodiments of the internal fortress. However, we are missing the point if we do not add to them, the quasi-totality of the built environment whose walls make sure to implement the segregation of included and excluded bodies.

Fortress North is a complex architectural and administrative structure that controls movement to the Global North and often prevents it, whether by exclusion or incarceration. Capitalism implemented the globalization of monetary and goods exchange in the world; it also facilitated the movement of its beneficiary but prevented the migration of its subjects with the help of architectural and territorial apparatuses whose budget could arguably be used alternatively to allow or even foster it instead.

Léopold Lambert is a Parisbased architect and editor of The Funambulist (http://thefunambulist.net) and its podcast, Archipelago (http://thearchipelago.net) that both attempts to raise questions around the politics of the built environment in relation to the bodies. He is the author of Weaponized Architecture: The Impossibility of Innocence (dprbarcelona, 2012), and Politique du Bulldozer (B2, forth coming 2015). In September 2015, he will launch the first issue of The Funambulist Magazine.

1cf. Léopold Lambert, Weaponized Architecture: The Impossibility of Innocence, Barcelona, dpr-barcelona, 2012, and The Funambulist Pamphlets Volume 6: Palestine, Brooklyn: punctum books, 2013.

Add new comment